Locking up approximately 1 percent of its adult population behind bars, the United States currently has the highest incarceration rate in the entire world. For many incarcerated individuals, a gubernatorial or presidential pardoning is their only chance at freedom. What does it take for a high-level authority in the United States to pardon a prisoner? We understand that inequalities contribute to the likelihood of someone becoming incarcerated. However, do these or similar inequalities also affect an incarcerated person’s chances at being pardoned? How does being ‘different’ affect a prisoner’s chances at being pardoned?

How did we answer this question?

With the American Philosophical Society’s digitized admission books from the years 1830 and 1850 at the Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP) in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, we wanted to measure the impact of such ‘differences’ on the likelihood an inmate at ESP would be pardoned. We were interested in connecting the past with our present in terms of understanding how personal biases permeate into ideas of the criminality and pardonability of inmates throughout time. This is constructive to unpacking our contemporary understanding of how such biases disproportionately affect inmates today. Tracing this history by understanding how ‘differences’ contributed to an inmates pardonability in the 19th century would perhaps offer us more insight into the pervasiveness of inequality in American prison systems.

As it is in most countries in the world, the “pardon” in the United States serves as a form of executive order by which a criminal’s conviction can be cleared completely along with a full commutation of their sentence. In Pennsylvania, since its entrance into statehood in 1776, the right to issue pardons has always belonged to the Governor even through several major revisions of the state’s constitution (specifically in 1790, 1838, 1874, 1967). Though the Pennsylvanian constitution did not initially define a clear process for the review of pardon applications, this process has become consistently more organized over the decades, as concerns for the transparency and fairness of the review process have remained central since the founding of the United States. Starting in 1874 and most recently in 1967, a system of checks and thorough investigation for pardoning was thus introduced more explicitly in the state’s constitutions.

As it is in most countries in the world, the “pardon” in the United States serves as a form of executive order by which a criminal’s conviction can be cleared completely along with a full commutation of their sentence. In Pennsylvania, since its entrance into statehood in 1776, the right to issue pardons has always belonged to the Governor even through several major revisions of the state’s constitution (specifically in 1790, 1838, 1874, 1967). Though the Pennsylvanian constitution did not initially define a clear process for the review of pardon applications, this process has become consistently more organized over the decades, as concerns for the transparency and fairness of the review process have remained central since the founding of the United States. Starting in 1874 and most recently in 1967, a system of checks and thorough investigation for pardoning was thus introduced more explicitly in the state’s constitutions.

Given that our research focuses on a time period between 1830 and 1850 in the Pennsylvanian pardon system, we cannot say for certain whether or not the pardoning process was as rigorous as it has been since 1874 in the state. Since the process for pardoning was not as systemized during the given time frame, one could expect that the personal sentiments of the Governor of Pennsylvania about the prisoners played a larger role in his decisions. Perhaps his personal biases—regarding ‘differences’ in characteristics like race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, etc.—were reflected in his view of a particular inmate’s ‘pardonability.’

For our research, we measured such ‘differences’ by disaggregating the ESP admissions book data on inmates by noting differences in gender, ethnicity, religion, and country of birth. Specifically, a difference in gender implied an inmate was notated to be female. A difference in ethnicity implies that an inmate was indicated as a “Black” or “Mulatto” person of color. A difference in religion implies that an inmate had an indicated religion in the admission book. A difference in country of birth implied an inmate was an immigrant and not born in the United States. Thus, an inmate who had no notation in the gender, ethnicity, or religion column and who also was born in the United States would have “no difference.” Our controls for each inmate were their number of convictions and their sentencing length. Running a regression on binary variables that noted our ‘differences’ with our controls, we were able to find the following correlations between these ‘differences’ and the ‘pardonability’ of inmates at ESP.

What did we find?

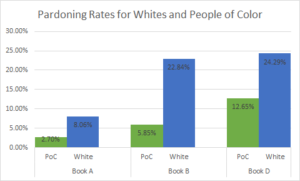

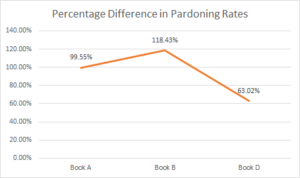

Admission Book A listed 520 inmates admitted into ESP from April 1830 to July 839. From our regression, we found that being a person of color was negatively correlated with being pardoned, with a more negative correlation than the number of convictions inmates had. Being a different religion was positively correlated with being pardoned. Additionally, being a person of color and having a different religion was positively correlated with having a longer sentence. Lastly, having a longer sentence was positively correlated with being pardoned.

Admission Book B listed 549 inmates admitted into ESP from August 1839 to May 1843. We had a similar finding from our results from Book A that being a person of color was negatively correlated with being pardoned. Being a different religion was also positively correlated with being pardoned, as was having a longer sentence. As with Book A, being a person of color was positively correlated with having a longer sentence.

Admission Book D listed 660 inmates admitted into ESP from March 1845 to April 1850. We had very similar results from the regressions we drew from Book A and Book D. Being a person of color was negatively correlated with being pardoned but positively correlated with having a longer sentence. Similarly, having a different religion was positively correlated with being pardoned and with having a longer sentence.

Over time a larger percent of inmates were pardoned at ESP from 1830 to 1850. However between Admission books A and B, the pardoning rate for ‘non-different’ white inmates increased much faster than that of ‘different’ inmates of color. Thus, while the system generally became forgiving, it increased its bias as depicted in the above graphs. Between Admission books B and D, the pardoning rate also increased over time, but it remained more uniform for ‘non-different’ white inmates and ‘different’ inmates of color.

For full code and results, please refer to this document.

What does this mean?

Our results from the data of each admissions book demonstrated that people of color were specifically less likely to be pardoned. Regressions ran on our control of sentence length demonstrated for all three books that people of color were also more likely to receive longer sentences. Thus, although inmates of color were likely to receive longer sentences for their crimes, they were less likely to receive a gubernatorial pardoning. Our results also found that having a longer sentence meant inmates were more likely to be pardoned. This makes sense, as perhaps inmates with short sentences were less likely to be pardoned, given that they could just serve their short sentences. Therefore, it is significant that despite being more likely to receive longer sentences, inmates of color were less likely to be pardoned from the years 1830 to 1850 in Pennsylvania.

What next?

The data from the American Philosophical Society’s historic prison data was far from perfect. Blank entries and discrepancies in the notation across the three books made it difficult for us to standardize our measure of ‘difference.’ We were also missing data on prisoners admitted into Eastern State Penitentiary from May 1843 to March 1845. Discovering this missing admissions data may add perhaps hundreds more data points to assess, which would give us better results from our regressions.

Additionally, while Admission Book A had a column that notated prisoners’ gender, the other two admission books did not. Therefore, we were only able to run regressions with a “difference in gender” on just under 30% of our total data. Because only 35 inmates were notated as “Female” in Admission Book A, our results were quite negligible. Perhaps to better this finding, we might consider running a separate regression on just female inmates at Eastern State Penitentiary from 1830 to 1850 to consider how their ‘differences’ beyond their gender might contribute to their pardonability.

Next steps for this particular project could include adding other measures of ‘difference’ such as socioeconomic status. This would require a more thorough assessment of the historic prison data and research into average income levels of specific professions held in the mid-19th century. Some data of interest in the expanded admission books could include occupation and literacy. Perhaps using race as a control variable, we could run regressions on inmates by their inferred socioeconomic status to see if we can draw any correlations between race, socioeconomic status, and pardonability.

Citations:

Beck, Allen J. and Bonczar, Thomas P. “Lifetime Likelihood of Going to State or Federal Prison.” Bureau of Justice Statistics, 6 March 1997, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/Llgsfp.pdf.

“Constitution of Pennsylvania – September 28, 1776.” The Avalon Project : Constitution of Pennsylvania – September 28, 1776, avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/pa08.asp.

“Constitution of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania – 1790.” The Constitution Party of Pennsylvania, www.constitutionpartypa.com/constitution-of-the-commonwealth-of-pennsylvania—1790.html.

“Constitution of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania – 1874.” The Constitution Party of Pennsylvania, www.constitutionpartypa.com/constitution-of-the-commonwealth-of-pennsylvania—1874.html.

Dembart, Lee. “MEANWHILE : The U.S. Founding Fathers Worried About Pardons.” International Herald Tribune, 20 Feb. 2001, https://www.nytimes.com/2001/02/20/opinion/IHT-meanwhile-the-us-founding-fathers-worried-about-pardons.html.

“United States profile.” Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/profiles/US.html.